Courtney Werner and Leah Wasacz, Monmouth University, COVID and Ideologies: Changing Identities on Writing Center Websites

Center Sites: Responding to COVID with Our Landing Pages

Dr. Courtney L. Werner, Monmouth University

Ms. Leah Wasacz, Monmouth University

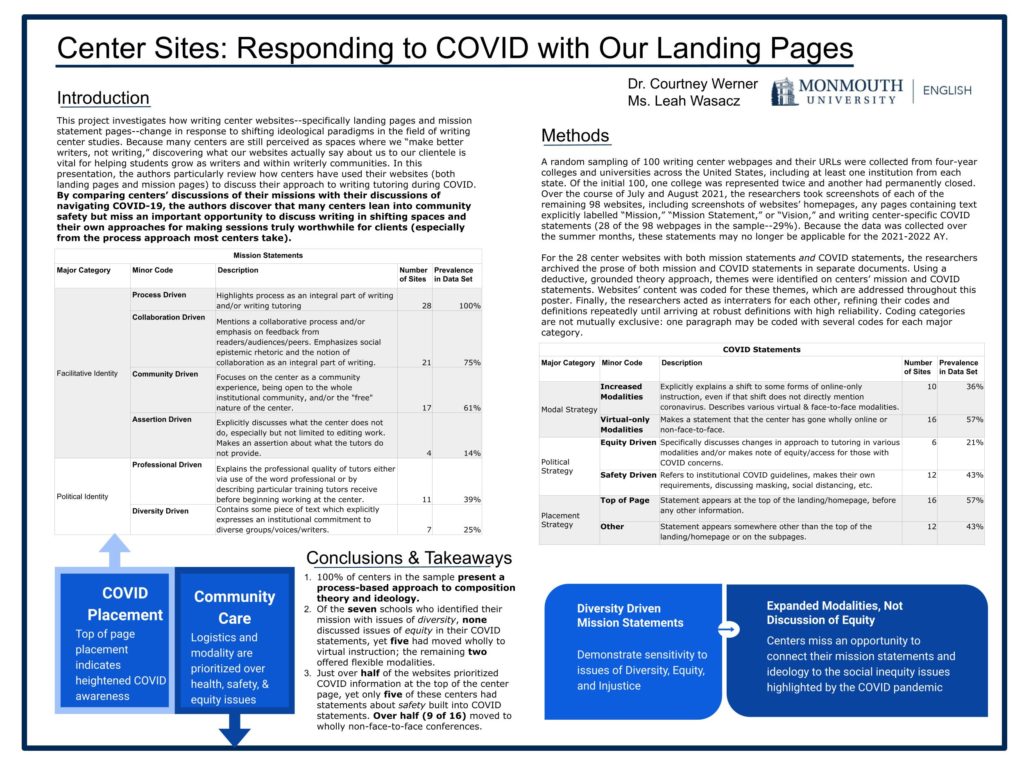

Below, we explain the results of our study comparing writing centers’ mission statements with their COVD-19 statements. Of 100 center websites examined, 28 had mission and COVID statements. Our study unpacks trends across these 28 center websites.

Defining Statements

Mission statements were defined as (1) any text on the website homepage or subpages explicitly labelled “Mission,” “Mission Statement” or “Vision,” or (2) any piece of primary text on the homepage introducing or summarizing the nature of the writing center. COVID statements were defined as any piece of text on the homepage or subpage that (1) directly refers to coronavirus or COVID-19 or (2) discusses a shift in the center’s operations, even if it did not directly mention COVID. Websites with institutional COVID banners were not included unless the writing center website explicitly had unique text fulfilling either (1) or (2). On the poster, Table 1: Mission Statements and Table 2: COVID Statements describe the coding categories and prevalence of each code in the sample.

Discussion

The ways these websites (de)prioritize and represent COVID-19 information, especially compared to mission statements, reflects their approach to tutoring and their commitment to stated values. By comparing centers’ mission statements with their COVID-19 statements, the authors discover most centers prioritize community safety but avoid ideologies and philosophies.

Of the mission statements sampled, 100% (28 websites) displayed a process-driven approach, suggesting process theory (Anson, 2014) is the core pedagogy. The University of Missouri center website states, “Although tutors are not editors, they can help with any stage of the writing process, from initial brainstorming, to major structural revisions, to putting the finishing touches on a final draft.” Other sites, such as the University of North Dakota’s, in emphasizing that “the development of writing abilities is a life-long process,” suggest that students are not merely improving one paper, but improving as writers (North, 1984).

Collaboration-driven strategies were common (75%, 21 websites), as were community-driven strategies (61%, 17 websites).The University of Jamestown mission statement says “Our center is a community of practice, facilitating relationships between students, faculty, and the Writing Center . . . As a community, we learn from each other’s experiences and expertise as well as from the experiences and expertise of our clients.” Jamestown establishes a vision of community-based writing and knowledge (Julier, Kingston, & Goldblatt, 2014) and collaboration (Bruffee, 1984).

39% of statements (11) are professionally driven (Bright, 2017; Jefferson, et al., 2009), drawing attention to tutors as trained “experts.” Franklin Pierce University states, “The [writing center] is staffed by trained, experienced peer writing partners available to support clients of all abilities from any course at any stage in the process…” It is likely these centers emphasize the professional nature of tutors to help “sell” the center or enculturate tutors.

Only seven statements (25%) are diversity driven even though DEI is a growing topic in writing center studies (Greenfield, 2019). These statements emphasize the role marginalization and identity play in writing/tutoring. The University of Wisconsin-Madison writing center’s statement stands out:

The Writing Center seeks to foster educational equity and is committed to social justice and inclusivity; however, we are coming to terms with the reality that these efforts are not enough. As part of an academic institution, we have been complicit in harm against students of color and have perpetuated anti-Black racism in our role as a gatekeeper of academic writing, which oftentimes perpetuates linguistic injustice. In response to calls to action from students within our department and across campus, we are rethinking our core practices and building on our recent inclusivity initiatives in order to decenter whiteness and center Black epistemological knowledge and practices. We will work to promote educational equity, foster social justice, and undo systems of oppression throughout the work that we do. We look forward to communicating more about these initiatives and practices as they progress.

The radical suggestion to flip the epistemological bases of writing–“decentering whiteness” and centering “black epistemological knowledge and practices”–articulates how centers can begin to address these concerns. Other centers dedicate less language to these ideas but still emphasize acknowledging diversity. The Rutgers University statement reads, “Because Rutgers is one of the most multicultural and linguistically-diverse universities in the country, our tutoring practices reflect this rich diversity.” While some centers integrate these ideas into their mission statements, the majority do not.

Contrasting COVID statements with diversity-driven mission statements shows a gap. Of the seven schools whose missions were coded as diversity-driven, none have equity-driven COVID statements. The University of Hawaii center COVID statement says, “In order to prioritize the health and safety of our student visitors, staff, faculty, and everyone’s ‘ohana, we have kept our tutoring services online for the Fall 2021 semester.” This equity-driven statement addresses the communal aspect of the pandemic in protecting everyone’s “‘ohana.” Access to safe tutoring and education is not only a matter of the individual, but also a matter of the family, broadly defined, and this statement emphasizes how individual safety cannot be divorced from the context of community safety and access.

Over half of the sample (57%, 16 websites) placed COVID information at the top of their webpages, prioritizing it over general center information/goals. Although over half of these sites (9 of 16) moved to online-only instruction, only five built statements about safety into their COVID information. One site coded as both safety- and diversity-driven statements, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champagne, says, “To protect the health and safety of our students, consultants, and community, all Writers Workshop services are being offered online.” This connection between diversity and safety is subtle, reflecting their connection. Overall, the placement and content of the COVID statements indicates that many centers did not connect community safety, access, and diversity.

This study suggests preliminary ways of seeing the data. Future research could consider larger samples of center mission statements or the ongoing response to COVID. Identifying how centers integrate concerns about pedagogy and ideology via their mission statements opens conversations for developing diverse communities of writers across institutions.

References

Anson, C. M. (2014). Process. A guide to composition pedagogies, 2nd Ed. Oxford, p.

212-230.

Bright, A. (2017). Cultivating Professional Writing Tutor Identities at a Two-Year College.

Praxis: A Writing Center Journal.

Brooks, J. (1991). Minimalist tutoring: Making the student do all the work. Writing Lab ‘

Newsletter, 15(6), 1-4.

Bruffee, K. A. (1984). Collaborative learning and the” conversation of mankind”. College

English, 46(7), 635-652.

Greenfield, L. (2019). Radical writing center praxis: A paradigm for ethical political

engagement. University Press of Colorado.

Jefferson, J., Cohn, A., Goldstein, E., Wallis, C., & Campbell, L. (2009). A Writer, an

Editor, an Instructor, and an Alumna Walk into the Writing Center. Praxis: A

Writing Center Journal.

Julier, L., K. Livingston, and E. Goldblatt (2014). Community-engaged pedagogies. A

guide to composition pedagogies, 2nd Ed. Oxford, p. 55-76.

North, S. M. (1984). The idea of a writing center. College English, 46(5), 433-446.

“Students’ right to their own language.” (1974). NCTE.